Position Papers

Small Children – Avoiding Choking Accidents: Warning Labels and Adult Supervision Work

Latex Allergies: Understanding Who’s at Risk

Balloon Litter: A Disintegrating Issue

Balloon Releases: Environmental Fact or Fiction?

Small Children – Avoiding Choking Accidents: Warning Labels and Adult Supervision Work

Even one child’s accidental death from choking on a latex balloon is unacceptable. The balloon industry emphatically agrees and every retailer, distributor and manufacturer is committed to helping create widespread public awareness among consumers in an effort to eliminate these needless events.

There’s still a way to go, but thankfully there’s been improvement. A look at the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) records from 1973 to 1998 shows that the number of annual small child choking deaths caused by balloons reached a high of 17 in 1989, but by 1998, the number was 4.

Warning Labels Are Effective

One key component in this decline in the accidental fatality rate is warning labels. The balloon industry has worked hard to increase awareness and educate consumers in how properly to use— and most importantly, dispose of — latex balloons.

This nationwide consumer awareness and education campaign began in 1992 when American balloon manufacturers took the lead and began placing prominent choking hazard warning labels on all balloon packaging. Designed to catch the attention of parents, this bold, conspicuously placed label clearly explains to all consumers that young toddlers — who will put anything in their mouths — could choke or suffocate on an uninflated balloon or balloon fragments. The warning pointedly encourages adults to supervise closely children under six when they are playing with balloons and to remove immediately uninflated balloons from the area and dispose of balloon pieces.

A 1991 national survey showed 27 percent of parents of young children were aware of choking hazards associated with latex balloons. Concurrently, the CPSC found that 43 percent of the industry’s balloon packaging had a warning label.

When the CPSC began in 1991 to explore avenues to reduce choking deaths that involved products not subject to the existing small parts test — which included latex balloons — the industry voluntarily pitched in and began reviewing its labeling practices.

As part of this evaluation mission, the newly formed industry voice — The Balloon Council (TBC) — began a collaborative effort with the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), a nationally respected, voluntary, standard-setting body. The purpose was to ensure that the industry produced standard packaging labels which were highly effective in communicating hazard potential to consumers. The CPSC was closely consulted during this development process.

Industry Sets the Standard

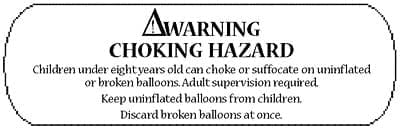

Interestingly, after extensive review, the CPSC rejected federally mandated warning labels because the commissioners questioned whether such labeling criteria would be any more effective than the industry’s voluntary standard. Ultimately the industry, with TBC assistance and CPSC support, instituted a highly readable and prominently displayed labeling policy. Since 1992, balloon packages sold by domestic manufacturers have carried a warning label:

Using the balloon industry warning label as a model, in 1994 the United States government enacted the Child Protection Act which mandates that balloons must have this warning conspicuously presented:

This type of label is critical to building consumer awareness and extending the education process because it reminds parents and guardians — from the outset — of the potential choking hazard that requires their immediate attention and close supervision.

Incident Reporting Law

The Child Safety Protection Act requires that any manufacturer, distributor, retailer or importer learning of a child who stopped breathing, required medical treatment, was injured or killed in an incident associated with their product, must file a timely report with CPSC.

This report must be filed within 24 hours after a company official — or employee — learns of the incident. These reports must be sent to: Directory of Corrective Actions, Consumer Products Safety Commission, Washington, DC 20207. The CPSC telephone number is 301-504-0608 and the fax number is 301-504-0359. This report also can be filed using the form provided on the CPSC’s Internet web site at: www.cpsc.gov.

Misinformation

Regrettably, in spite of the industry’s education efforts, misinformation about balloons and choking continues to be spread within many different segments of the country.

One highly visible segment is the nation’s hospitals. Originally, hospitals across the country began banning latex balloons in patient areas out of fear of a child choking. This growing trend was based on over-inflated child choking figures and unsubstantiated allegations such as: “Latex balloon are the leading cause of deaths associated with toys.” This is a wholly misleading representation of the facts compiled and reported by the CPSC in its detailed annual statistical data summations.

Some hospitals and newspapers went further in 1994, stating: “The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission reports that balloons account for 43 percent of all childhood deaths related to children’s products.”

In addition to contacting every hospital TBC learned was involved in this misstatement, TBC contacted the CPSC to challenge this statement. The CPSC’s chairman at that time readily acknowledged the statement’s incorrectness and provided assurances the CPSC was not the source.

Facts

For the record, the leading causes of toy-related deaths for many years have been “wheeled toys” in the reports issued by the National Safety Council, From 1985 to 1996, at least 155 children ages 0 to 14 died in go-cart accidents alone while 98 child deaths were attributed to choking on balloons over those 11 years.

The balloon industry is intent on providing products that are fun and safe for everyone and don’t conflict with the environment. Industry leaders also recognize they have obligations to set industry standards that will help protect and preserve the environment and provide consumers with information that will encourage them to use the product safely and responsibly and dispose of it properly.

Prominent labeling coupled with increased public awaeness and close adult supervision has helped cut the young child mortality rate by almost 50 percent.

Latex Allergies: Understanding Who’s at Risk

Latex allergies present a moderate to serious health problem for a small percentage of the population in the United States. Unfortunately, public communications of the latex allergy facts often are mishandled and misleading, causing unnecessary alarm and controversy about latex balloons among the majority of us.

However, the American public can rest assured— they’ll not find the lovable latex balloon anywhere near the heart of the latex allergy problem. Here’s the situation:

Small Percentage of Population At Risk

Latex is the milky sap produced by rubber trees. Like many other natural things — bee sting venom, poison ivy, peanuts — latex can cause allergy problems ranging from minor skin irritation to reactions so severe that immediate emergency medical treatment is required to prevent death.

According to the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Journal of the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists, 94 percent of us probably will never have an allergic (anaphylactic) reaction to latex balloons.

Oddly enough, those most at risk of having an allergic reaction to latex are found in hospitals — doctors, nurses and certain patients.

Old Problem or New?

Although first developed in the middle 1800s, latex didn’t become widely used until the early 1940s. But, it took almost four decades before allergic reactions started appearing and causing problems.

The first latex allergy report occurred in Great Britain in 1979 — a woman’s reaction to household rubber gloves. Only 50 documented cases were reported in Europe over the next nine years.

Late in 1989, the FDA started receiving reports of patients going into allergic shock during radiological examinations. In each case, the culprit proved to be invasive diagnostic and treatment equipment which used latex components that came into contact with patients for a long period of time. The latex components were universally replaced.

Then, between 1990 and 1991, severe allergic reactions erupted in some 84 children at 25 pediatric hospitals and eight required intensive care. Fortunately none died. These children had either spina bifida or conditions involving the genitourinary tract. According to Dr. Michele Pearson, an epidemiologist with the National Centers for Disease Control, all these children had been exposed to anesthesia equipment and intravenous catheters that incorporated latex parts which came in close constant contact with skin. The FDA subsequently issued an urgent alarm nationwide to 1,000 health care leaders in March 1991.

1991 also saw rapidly increasing incidents of allergic reactions reported among doctors, dentists, nurses and health care technicians.

Latex has been used widely in everyday items for decades. What was happening to cause this hyper sensitivity and why so many incidents so suddenly? To date, no concrete conclusions have been reached, but two situations occurred almost simultaneously which may have helped initiate the problem:

- During the early 1980s, AIDS cases were accelerating at an alarming rate. The health care industry came to realize exactly how this disease could be transmitted — especially to doctors, dentists, nurses and technicians treating these patients. In 1991, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) mandated that all health care workers must wear protective surgical gloves while caring for all patients. Because of its superior barrier and sensitivity properties latex is the material of choice throughout the health care industry — latex glove use jumped from 2.5 billion in 1985 to more than 15.4 billion by 1995. Consequently, health care workers (especially emergency care workers) are wearing latex gloves more often and for much longer periods of time — causing existing sensitivities to surface, or creating new antibodies. The problem is made worse because wearers are aggressive in removing gloves, spreading the powder inside which carries latex molecules.

- Another possible contributing factor to the hyper-sensitivity is that latex manufacturers may not have been allotting enough time on the production line for a complete and thorough washing which will remove many of latex’s allergy-triggering proteins. Although the FDA has no concrete evidence of this, the agency now requires all latex glove manufacturers to follow a stringent two-step washing procedure.

Today, health care experts estimate that one to six percent of the general population is sensitive to latex — comparable to the rate for bee venom, peanuts, grass and animal hair.

However, within the health care industry population segment there is a dramatic surge above the norm with sensitivity rates ranging from 8 to 14 percent. The highest at-risk population segment is children with spina bifida who have an exorbitantly high sensitivity rate of 25 percent.

An Equally Enjoyable, No-Risk Option

While the balloon industry is cooperating with the health care industry on this issue, patients — especially children — aren’t losing out on the joy and entertainment balloons bring to a hospital room. Since the late 1970s, the balloon industry and its retailers have been providing synthetic, metallized balloons — commonly known as mylar — that offer a wide range of festive colors, unique shapes and messages that make people feel good.

An Interesting Side Note

Ansell Perry Healthcare, the foremost international maker of latex surgical gloves, is a direct corporate descendent of one of the nation’s first major balloon manufacturers. The company — through a program called AnsellCares — is underwriting an aggressive, leading-edge, scientific research to isolate and eliminate the health care industry’s latex allergy problem.

The balloon industry is intent on providing products that are fun and safe for everyone and don’t conflict with the environment. Industry leaders recognize they have obligations to set industry operating standards that will help protect and preserve the environment, and provide consumers with information that will encourage them to use the product safely and responsibly and dispose of it properly.

Balloon Litter: A Disintegrating Issue

The balloon industry operates with an eye on the environment. Manufacturers try to ensure both the organic materials harvested and the production processes are environmentally sound. Retailers — mostly family-owned and operated small businesses — try to ensure their products are handled properly by informed consumers. The industry’s efforts are paying off.

According to the annual International Coastal Cleanup report prepared by the Center for Marine Conservation, balloon litter on the nation’s riverbanks and beaches has been steadily declining since 1993. However, in spite of this consistent downward trend, there have been ongoing claims and assertions that balloons, especially those used in releases, are a major source of litter in these areas.

Is balloon litter really a significant ecological issue? Let’s examine the facts.

Balloon Construction

Two distinctly different types of balloons are manufactured and sold in America today — latex and mylar.

Latex balloons are produced from the sap of the rubber tree. It is collected without harming the tree by using an environmentally safe, age-old process similar to that used for collecting the sap from maple trees for syrup. Because of rubber’s versatility and demand, these tropical rain forest trees are very valuable, highly coveted — and well-protected natural resources. These precious trees play an equally valuable ecological role in the earth’s fragile ecological balance by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere which helps prevent global warming.

A latex balloon is made from 100 percent organic material and it’s 100 percent biodegradable. Stress caused by inflation starts this decomposition cycle. Exposure to sunlight accelerates the process — oxygen and ozone continue the molecular attack even in the dark. Deterioration is clearly evident within a few hours — it begins to oxidize or “frost” — and soon the balloon will break apart. Research has shown that under similar conditions latex decomposes as quickly as an oak leaf.

The second type of balloon sold in the United States is commonly — but incorrectly — called mylar. It’s made from a metallized nylon (plastic) that is not biodegradable. Better known as silver balloons, they are much more expensive than their latex cousins and are never used in balloon releases.

Balloon Releases – Unjustified Concern

Mass balloon releases come under fire from misinformed critics who inaccurately claim releases generate a major source of litter and threaten the ecology. While anecdotal, subjective “evidence” is usually cited to support these assertions, corroborating factual data is rarely presented.

Important facts you should know about latex balloon releases:

- Only latex balloons are used by professionals in mass releases. Industry guidelines require these balloons to be self-tied and have no attached strings or ribbons — each released balloon is 100 percent biodegradable.

- Rarely do released balloons return to the earth’s surface intact. Studies show these balloons usually rise to an altitude of about five miles. At that point, freezing and air pressure causes “brittle fracture” creating spaghetti-like pieces that scatter to the four winds.

- While some balloons don’t reach this altitude, research indicates that in an average 500-balloon release, the unexploded balloon return density is no greater than one per 15 square miles.

- Research shows that regardless of the latex balloon’s ultimate form when it lands, it will decompose, forming a natural soil nutrient at the same rate as that of an oak leaf.

Dropping to Bottom of Litter List

In 1986 the Center for Marine Conservation (CMC) began a volunteer coastal cleanup program in Texas, went national in 1988 and international in 1989. Today, this campaign is known as the International Coastal Cleanup. In the United States it now involves more than 160,000 volunteers, who scoured 6,887 miles of beaches, oceans and waterways as part of the world’s largest marine trash haul.

In addition to removing debris from inland beaches, shorelines and waterways as well as underwater areas, the CMC collects and maintains detailed data on the types and amounts of debris removed each year. Even a casual look at this data reveals a downward trend in balloon litter which indicates balloon disposal labeling and good release management practices are working.

In 1994, the CMC’s U.S. Coastal Cleanup involved 139,746 volunteers and covered 5,200 shoreline and underwater miles. Balloons/balloon pieces were found at a rate of 6.93 per mile and accounted for .64 percent of the total debris collected — which resulted in balloons ranking 27th on the CMC’s list of 80 common items.

By 1998, the CMC’s U.S. Coastal Cleanup grew to include 160,000 volunteers and covered 6,887 miles. Although the manpower and coverage increased so dramatically in 1997, the amount of balloons/balloon pieces found decreased to a rate of 5.5 per mile.

That’s improvement.

The CMC‘s 1999 Coastal Cleanup occurred in September, but the debris data will not be available until the second quarter of 2000.

Bottom line — balloon litter has never been a significant part of the list of debris and it continues to drop towards the bottom of the CMC list. In 1994 balloons were ranked 27th and in 1997 balloons had fallen to 37th. This declining trend coincides with the industry’s public education programs and is evidence that the packaging information about proper disposal and release of balloon is working.

Carelessness Happens

However, a closer look at the make-up of the balloon litter found during these annual campaigns tells us the industry must continue to build consumer awareness through public education. For example, the makeup of the majority of balloons found during the cleanups are not the result of mass releases. In one Florida-wide cleanup there were 288 balloons/balloon pieces found. Of these:

- 79 were water balloons which obviously are not used in releases

- 38 were too small to have been released

- 96 had strings/ribbon/thread attached (never used in a release)

- 2 were valved (never used in a qualified release)

- 3 were shaped (never used in a qualified release)

- 70 — less than 25 percent — might have been used in releases

Objectively judging the cleanup data and applying common sense, most open-minded observers examining the facts will arrive at the conclusion that balloons — including mass balloon releases — do not constitute a serious litter or ecological problem. The majority of balloon litter is caused through either accident or carelessness.

Even so, public and regulatory agency perceptions are critical and the balloon industry is working to increase consumers awareness of good balloon use, safety and disposal management . The industry’s goal is to remove balloons from the CMC Coastal Cleanup litter list. Here’s what the industry is doing to reach this goal.

Consumer Education Ongoing

Balloon manufacturers and distributors are working alongside retailers to educate consumers and create awareness of the value of good balloon management practices. This is being accomplished through an ever-expanding campaign of informative messages attached to balloon bouquets and printed on balloon packages and in-store information. Specifically, these messages are:

- Follow industry guidelines for balloon releases — use only hand-tied latex balloons and no plastic attachments

- Never release mylar balloons

- Never attach metallic ribbon to helium-filled balloons. An accidental release could become tangled in power lines and might cause a line fault

- Always supervise young children under age 8. Never allow children to play with deflated balloons — or broken pieces — which could cause choking or suffocation

- Always attach weights — mug, vase or heavy object — to helium-filled balloons to counter lift and prevent accidental release

- Don’t tie helium-filled mylar balloons together and ensure each is individually attached to a counter-weight to prevent them from rising as a cluster which could catch on power lines.

- Properly dispose of balloons. Cut balloons with scissors directly above the knot or sealing point and immediately place in trash containers.

The balloon industry is intent on providing products that are fun and safe for everyone and don’t conflict with the environment. Industry leaders also recognize they have obligations to set industry standards that will help protect and preserve the environment, and provide consumers with information that will encourage them to use the product safely and responsibly and dispose of it properly.

Balloon Releases: Environmental Fact or Fiction?

Erroneous reports about balloons and balloon releases harming the environment have appeared in major newspapers and on national TV news programs. Many of these reports contain inaccurate claims made by well-intentioned people who care deeply about the earth’s ecology — but lack the facts.

Balloons used in special event releases constitute only a small fraction of the industry’s sales. Unfortunately, these spurious claims have caused a chilling effect at the local level and unnecessary financial strain on many of America’s small, independent balloon retailers who depend on special events as a major source of their livelihoods. Small industries such as delivery and decorating services also suffer.

Most consumers don’t have the time or inclination to sort through bad information disguised as fact — often resulting in a negative perception that balloons are bad.

Latex balloons are sometimes confused with plastic items and lumped in with the plastics litter problem. The oft-used phrase, “latex balloons and other plastics” is improper. Latex is not a plastic. It’s organic, made from the sap of rubber trees collected through an absolutely harmless tapping process very simple to that used for collecting the maple sap used for making syrup.

Moreover, latex balloons are totally biodegradable — the only type of balloon used in a professionally-produced mass release. A latex balloon’s molecular structure begins breaking down with inflation and gathers momentum when exposed to sunlight and the atmosphere. Within three hours, most latex balloons released into the atmosphere rise to approximately five miles, begin to oxidize, freeze and shatter into spaghetti-like pieces. Once on the ground gases and microorganisms attack the latex, continuing the natural decomposition process — even in the dark.

Scientific research, most notably by D.K. Burchette in, “A Study of the Effect of Balloon Releases on the Environment,” demonstrates that latex balloons decompose at a rate equal to — or faster than — an oak leaf under similar conditions.

Mylar balloons are foil-like, usually silver and cost significantly more (retailing for $3 – $8 each) than latex balloons. Mylar is a synthetic, metallized plastic/nylon material which is recyclable, but not biodegradable. Consequently, mylar balloons are never used in a release.

Helium-filled mylar balloons do get away accidentally because a string breaks or a consumer lets go. These incidents seem to be diminishing as a result of ongoing in-store awareness campaigns to encourage anchoring these balloons with decorative weights.

Industry Release Standards

The American balloon industry has set firm standards for mass balloon releases.

- Releases must use only 100 percent latex balloons

- All attachments must be biodegradable

- All balloons must be self-tied

- Balloons cannot be attached to each other

Balloons and Sea Animals

Since the mid-1980s, many have raised alarm and hyped rumors that balloons are a constant threat to sea animals, causing a plethora of deaths. Most often this misinformation can be traced to two incidents which occurred along the New Jersey coastline back in the 1980s.

The first incident was in 1985. A 17-foot whale was severely injured after it got stuck within the pilings of a pier and subsequently died. Although the actual cause of death was never scientifically established, the post-mortem revealed a deflated mylar balloon attached to three feet of ribbon in the whale’s stomach. Balloon release opponents frequently claim this was the cause of death. Perhaps, but this incident doesn’t support the anti-release position because neither mylar balloons or ribbons are used in releases.

No direct cause of death was determined by authorities in the second incident which occurred in 1987 and involved a leatherback turtle.. When discovered, the turtle was so decomposed that gender could not be determined. It did have a three-foot long wound caused by a boat propeller — a common cause of sea animal injury and mortality — and the neck of a latex balloon attached to three feet of ribbon also was found in the intestines. This latex balloon did not come from a release — professionally released balloons do not have ribbon attached. Once again, this incident is irrelevant to the anti-release argument.

Until 1997, TBC studies of public incident records and academic research pertaining to balloon releases produced no other incidents of sea animal deaths or injury cases caused by balloons. With one exception occurring in 1996, those presenting this “evidence” have never produced scientific documentation to substantiate these allegations.

The University of Texas Marine Science Institute produced some turtle mortality research in which balloon pieces were found in about six percent of the animals examined. However, chief researcher Pamela Plotkin unequivocally stated that balloons were not the cause of these turtle deaths.

Dr. George Balazs of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Marine Fisheries Service is often cited by balloon release opponents. However, Dr. Balazs has never claimed that a balloon caused the death of any sea animal, even though he has found balloon pieces during several necropsies.

The one exception to the rule was documented on The Discovery Channel in 1997. Marine scientists rescued a sick whale off the Florida coast. During an exploratory surgical procedure, the scientists found and removed a deflated latex balloon blocking the digestive tract leading into the second stomach. The whale subsequently recovered and was released back into the ocean.

In pursuing the facts, TBC also has conducted two extensive database searches. These searches examined documented turtle deaths along the U.S. coastline from Maine to Texas during the 1980s. The results of this investigation: only one report of a balloon being swallowed — the New Jersey leatherback turtle incident described earlier.

Typical of the information contained in these databases is the 1988 database which documents 284 incidents in the Northeast. The most significant causes of death were from boat hits and propeller wounds (79). There were 17 ingestion incidents — not one was attributed to balloons.

A study by wildlife researcher Cathy Beck, published in “The Marine Pollution Bulletin,” found no balloons involved in the deaths of more than 800 sea cows examined over an eight-year period.

In summary, after extensive review of goverment and environmental databases, searches on the Internet, following up media reports and checking facts covering the period 1980 to 1998, TBC found:

- One scientifically documented incident in which a sea animal was harmed by a latex balloon

- No direct scientific evidence that any sea animal has been harmed or killed by a latex balloon involved in a release

- In one 10-year period, more than 100,000 sea turtles were killed by shrimp trawlers

Minuscule Litter Threat

The balloon industry operates with a vigilant eye on the environment. With concerns for the environment continuing to grow, the ongoing question that must be addressed by the balloon industry is: “Are balloons really a significant litter problem and ecological hazard?” The answer, according to the facts produced by independent organizations, is a resounding, “no.” Manufacturers try to ensure both the organic materials harvested and the production processes are environmentally sound. Retailers — mostly family-owned and operated small businesses — try to ensure their products are handled properly. The industry’s efforts are paying off.

Take a walk through your neighborhood, a local park or the woods. Most likely you’ll see a lot of litter — discarded cans, bottles, paper and plastic items. Odds are, you’ll rarely discover a latex balloon in this mess. And if you do, most likely it didn’t get there as a result of a mass release.

According to the Burchette report cited earlier, the vast majority of released balloons don’t even return to earth as balloons. Burchette’s study shows that the effects of altitude pressure and freezing causes “brittle fracture” — breaking into spaghetti-like pieces that scatter as they return to earth.

Burchette also studied the rate at which balloons fail to rise to this altitude due to leaks or underinflation. He found that in a average release of 500 balloons, the density of balloons landing intact would be no greater than one per 15 square miles.

According to the annual International Coastal Cleanup report prepared by the Center for Marine Conservation (CMC), balloon litter has been declining steadily.

In 1994, the CMC U.S. Coastal Cleanup found balloons/balloon pieces were found at a rate of 6.93 per mile and accounted for .64 percent of the total debris collected.

By 1998, the CMC’s U.S. Coastal Cleanup grew to include 160,000 volunteers and covered 6,887 miles. Although the manpower and coverage increased so dramatically in 1997, the amount of balloons/balloon pieces found decreased to a rate of 5.5 per mile. Balloons pieces found would fit inside five large garbage bags.

Bottom line — balloon litter has never been a significant part of the list of debris and it continues to drop towards the bottom of the CMC list. In 1994 balloons were ranked 27th and in 1997 balloons had fallen to 37th. This declining trend coincides with the industry’s public education programs and is evidence that the packaging information about proper disposal and release of balloons is working.

However, a closer look at the make-up of the balloon litter found in during these annual campaigns tells us the industry must continue to build consumer awareness through public education. For example. A close look at the makeup of the majority of balloons found during the cleanups clearly are not the result of mass releases. In one Florida-wide cleanup there were 288 balloons/balloon pieces found. Of these:

- 179 were water balloons which obviously are not used in releases

- 138 were too small to have been released

- 196 had strings/ribbon/thread attached (never used in a release)

- 12 were valved (never used in a qualified release)

- 13 were shaped (never used in a qualified release)

- 170 — less than 25 percent — might have been used in releases

Objectively judging the cleanup data and applying common sense, most open-minded observers examining the facts will arrive at the same conclusion: balloons —and mass balloon releases — do not constitute a serious litter problem or ecological threat.

Unjustified Environmental Concern

Latex balloons used in mass releases are produced from the sap of the rubber tree. It’s collected without harming the tree by using an environmentally safe, age-old process similar to that used for collecting the sap from maple trees for making syrup.

Because of rubber’s versatility and high demand, these tropical rain forest trees are very valuable and highly coveted. Equally important, these precious trees play a key role in the earth’s fragile ecological balance by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere which helps prevent global warming. As a result, the world’s rubber trees are well-protected natural resources.

Consequently, a latex balloon — the only type used in mass releases — is made from 100 percent organic material and it’s 100 percent biodegradable. Stress caused by inflation starts this decomposition cycle. Exposure to sunlight accelerates the process — oxygen and ozone continue the molecular attack even in the dark. Deterioration is clearly evident within a few hours — it begins to oxidize or “frost” — and soon the balloon will break apart into small pieces. Research has shown that under the same conditions latex decomposes as quickly as an oak leaf.

While the annual CMC Internatinal Coastal Cleanup campaign has been increasing in scope-manpower and coverage-balloons/balloon pieces represent a miniscule fragment of the tptal debris collected. In 1997, a record-setting year for the campaign, the quantity of balloons/balloon pieces collected declined for the second consecutive year.

Consumer Education Ongoing

Balloon manufacturers and distributors are working alongside retailers to educate consumers and create awareness of the value of good balloon management practices. This is being accomplished through an ever-expanding campaign of informative messages attached to balloon bouquets and printed on balloon packages and in-store information. Specifically, these messages are:

- Follow industry guidelines for balloon releases – use only hand-tied latex balloons and no plastic attachments

- Never release metallic balloons

- Never attach metallic ribbon to helium-filled balloons. An accidental release could become tangled in power lines and might cause a line fault

- Always supervise young children under age 8. Never allow children to play with deflated balloons – or broken pieces – which could cause choking or suffocation

- Always attach weights – mug, vase or heavy object – to helium-filled balloons to counter lift and prevent accidental release

- Don’t tie helium-filled metallic balloons together and insure each is individually attached to a counter-weight to prevent them from rising as a cluster which could catch on power lines.

- Properly dispose of balloons. Cut balloons with scissors directly above the knot or sealing point and immediately place in trash containers.

Conclusions

- The industry has attempted to collect all documented evidence and research covering the last 18 years which addresses the environmental and litter issues pertaining to balloons and mass releases.

- This data shows only one substantiated incident in which a sea animal was harmed by a latex balloon.

- This data shows no sea animal deaths due to a balloon.

- Latex balloons are 100 percent organic, 100 biodegradable and decompose at a rate equal to that of an oak leaf.

- On average, mass balloon releases have a return-to-earth rate of no greater than one balloon per 15 square miles.

- Total debris collected during annual CMC U.S. coastal cleanup campaigns from 1994 to 1997 averaged balloons/pieces content of .61 percent and this ratio is steadily decreasing. In 1997 — the largest CMC cleanup by far — balloons accounted for only .52 percent.

- The industry’s goal is to remove balloons from the CMC Coastal Cleanup litter list through ongoing consumer education and balloon management practices emphasized through package labeling and at point-of-purchase.

The balloon industry is intent on providing products that are fun and safe for everyone and don’t conflict with the environment. Industry leaders also recognize they have obligations to set industry standards that will help protect and preserve the environment and provide consumers with information that will encourage them to use the product safely and responsibly and dispose of it properly.